On average, new cars have gotten bigger between 2008 and 2015 by about 1 square foot (0.9 square meters / 2%) since the EPA has started keeping track of the rectangle formed by a vehicle’s wheelbase and track width, aka its “footprint”.

Despite SUVs growing in both size and numbers, Autonews reports that car manufacturers are also incentivized to make cars a little bit larger, thanks to “more forgiving fuel economy targets.”

Currently, the so-called National Program assigns both mpg and CO2 emission targets to vehicles based on the previously mentioned footprint, requiring annual improvements in efficiency for every footprint size. There are also different “curves” – such as for cars and for light trucks, where smaller vehicles have to deal with more stringent targets than larger ones.

What this means for manufacturers is that adding just a couple of inches to a new model’s wheelbase can result in a lower mpg target. In other words, automakers can build new cars that still get better fuel economy than their predecessors, without being pressured into hitting any unrealistic fuel economy targets.

“Cars are changing their dimensions in order to take advantage of this, but I don’t think it’s anything new,” said Dave Sullivan, an analyst with AutoPacific Inc. “We’ve been using every available credit or loophole that the system allows for years now.”

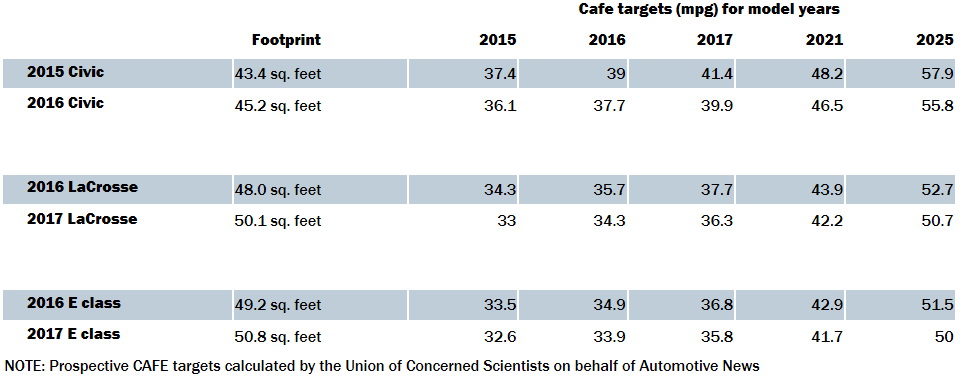

For example, take the new E-Class, Civic or the Buick LaCrosse. The latter is 2.7 inches (6.8 cm) longer between the wheels and 1.2 inches (3 cm) wider. This also boosts its footprint to 50.1 square feet (4.65 sq meters) – leading to a 2017MY target of 36.3 mpg (6.4 l/100km) under the US government’s corporate average fuel economy (CAFE) rules.

While this is more than the previous model’s 35.7 mpg (6.58 l/100km) CAFE target, it also happens to be 1.4 mpg less than the 37.7 mpg (6.2 l/100km) it would have had to average had GM continued to market the 2016 LaCrosse as a 2017 model year.

There are many others examples like the LaCrosse – from regular cars to pickups, large and small, from luxury and mainstream brands alike.

“Increasing a car’s footprint is a straightforward and reasonably inexpensive way” for dealing with annual targets, said Steve Skerlos, an engineering professor and researcher at the University of Michigan. “Having this option gives consumers what they want while lowering their targets, which means lower expenditures on the other fuel-saving approaches.”

However, according to Dave Cooke, an analyst with the Union of Concerned Scientists, the bigger footprint actually has a very limited impact since these types of changes can only occur once every five or six years, depending on a current model’s life cycle – reducing standards by 1 or 2 mpg.