There are so many variables to take into account when it comes to pedestrians. Human drivers know this all too well.

We are quite adept at recognizing whether a person intends to cross the street or is just standing by the crosswalk for no reason, we know what it means when a bicyclist gets into his or her pedaling motion, and we can gauge the pace of a jogger as they approach an intersection, anticipating whether they plan on continuing their run or if they will actually slow down.

Now, unless your computer’s name is Ultron or Skynet, odds are it’s not going to take these types of variables into account, at least not with such intuition as the one displayed by humans and certainly not with 2018 tech.

“You can’t stop for every human being standing by the side of the road,” stated Volvo R&D boss Henrik Green. “But you also need to stop at the right point when the pedestrian is about to step into the street.”

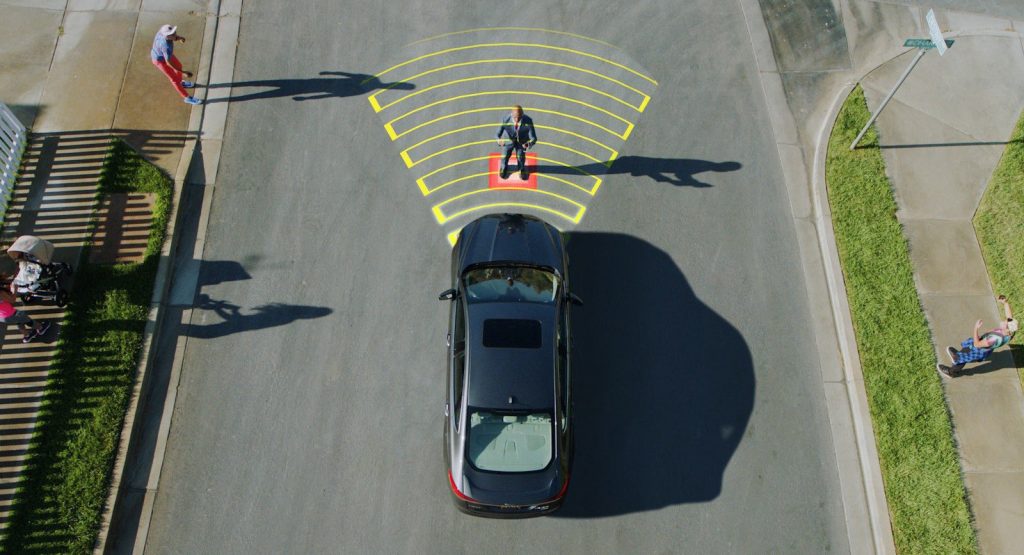

During this year’s LA Auto Show, Volvo and Luminar demonstrated how advanced their LiDAR technology is, as it can even detect human poses, including individual limbs, at distances of up to 250 meters (820 feet).

Even if sensors become exceedingly good at detecting motion, that alone may not be enough to give an accurate prediction of what could happen. For example, if a jogger has been detected for three seconds running towards an intersection, the best prediction for future intent may not be that exact trajectory, but rather their face and whether or not they were looking at the vehicle. Another good example would be if a pedestrian is detected looking down at their smartphone – such a thing would constitute a higher probability of risky behavior, reports Automotive News.

“The important thing is to understand these sorts of features rather than just looking at movement,” stated Leslie Nooteboom, co-founder and chief design officer at Humanising Autonomy in the UK.

Aside from software engineers, Humanising Autonomy also employs a team of behavioral psychologists who shift through camera footage and help train systems on how people behave when it comes to interacting with traffic.

“You have to have general behavior models that are very detailed, and then the next step is to make them more localized,” added Nooteboom. “We have a foundation of general behaviors for a particular city, and then you can link to specific locations and identify how people will behave at an intersection with an obscured stoplight or a crossing that stops in the middle of the road.”

Bottom line, self-driving systems pretty much cannot afford to predict human behavior incorrectly. As Pete Rander, president of Argo AI puts it: “If you don’t predict well, you have two options and neither of them are good enough. You’re either left playing it safe and creating a much more cautious bubble around you. Or you’re slamming on the brakes.”