Ayrton Senna’s victory at the Monaco Grand Prix in May 1992 was a particularly sweet one for McLaren, and not just because the team had finally broken Brit Nigel Mansell’s five-race winning streak.

Monaco was where McLaren was unveiling its brand new road car. And though legendary commentator Murray Walker ranked the ’92 race as one of his F1 favorites, in no small part thanks to the duel between Senna and Mansell, three decades later it’s proved nowhere near as significant as the F1 supercar.

What’s incredible about the F1 is that it seems almost as wild today as it did 30 years go because it moved the supercar needle so far, it completely fell off the dial. It was faster, more powerful, more expensive and more exotic than any supercar of the time. It had a funky three-seat layout and its top speed record stood for over a decade. And if auction values are anything to go by it’s shaping up to be even more collectible than the legendary Ferrari 250 GTO in the coming years.

So hitch a ride as we celebrate 30 years of the McLaren F1, remembering some famous facts, and maybe uncovering a few that you didn’t know.

1. The F1 wasn’t McLaren’s first supercar

Related: This Is What $150 Million Worth Of McLaren F1s Look Like

Back in the late 1960s, McLaren founder Bruce McLaren had a plan to develop a road-legal coupe based on his M6A Can Am cars that would also win on the track. Those plans were thwarted by the FIA’s insistence that McLaren build more completed cars than it was capable of, and then permanently laid to rest after Bruce’s fatal crash at Goodwood in 1970. But two road cars, including one that Bruce used as his own, were constructed.

2. The idea was dreamed up in an airport lounge

The origins of the F1 project can be traced to a conversation between McLaren chairman Ron Dennis, director Mansour Ojjeh, technical director Gordon Murray and head of marketing Creighton Brown while waiting for a flight in Milan in 1988. While most co-workers might talk football results and moan about their wives, these guys decided to build the world’s craziest supercar. And just four years later it was ready.

3. It wasn’t the first carbon supercar

McLaren pioneered the use of carbon fiber in F1, so it was only natural that the F1 road car would be built from the same stuff. Even so, Jaguar’s TWR-developed XJR-15 of 1990 was technically the first all-carbon supercar, but that was a thinly disguised racing car that existed only for homologation purposes, whereas the F1 was a dedicated road car.

4. It cost twice as much as its Bugatti EB110 rival when new

The F1 was priced at £634,500 including taxes in England in 1994 (equivalent to £1.08 m/$1.37 m today), when a Ferrari 512 TR cost £131,000, and even a Bugatti EB110 GT would only set you back £285,500.

5. But you could carry 50 per cent more people than in a 512 TR or Bugatti

The F1’s center-mounted driver’s seating position came from the racing world and meant a perfect pedal layout with no wheel arch intrusion and an optimal weight distribution, though getting in and out was tricky.

Having a passenger seat either side of that driver’s seat was unusual, but the setup was borrowed from Pininfarina’s mid-engined Ferrari 365 P Berlinetta Speciale, two of which were built, including one commissioned by Fiat boss Gianni Agnelli.

6. And you did at least get a free watch for your dough

Each F1 road car buyer received a special Tag Heuer watch with the car’s serial number marked on the face. Similar watches without the chassis numbers were also available for non-owners.

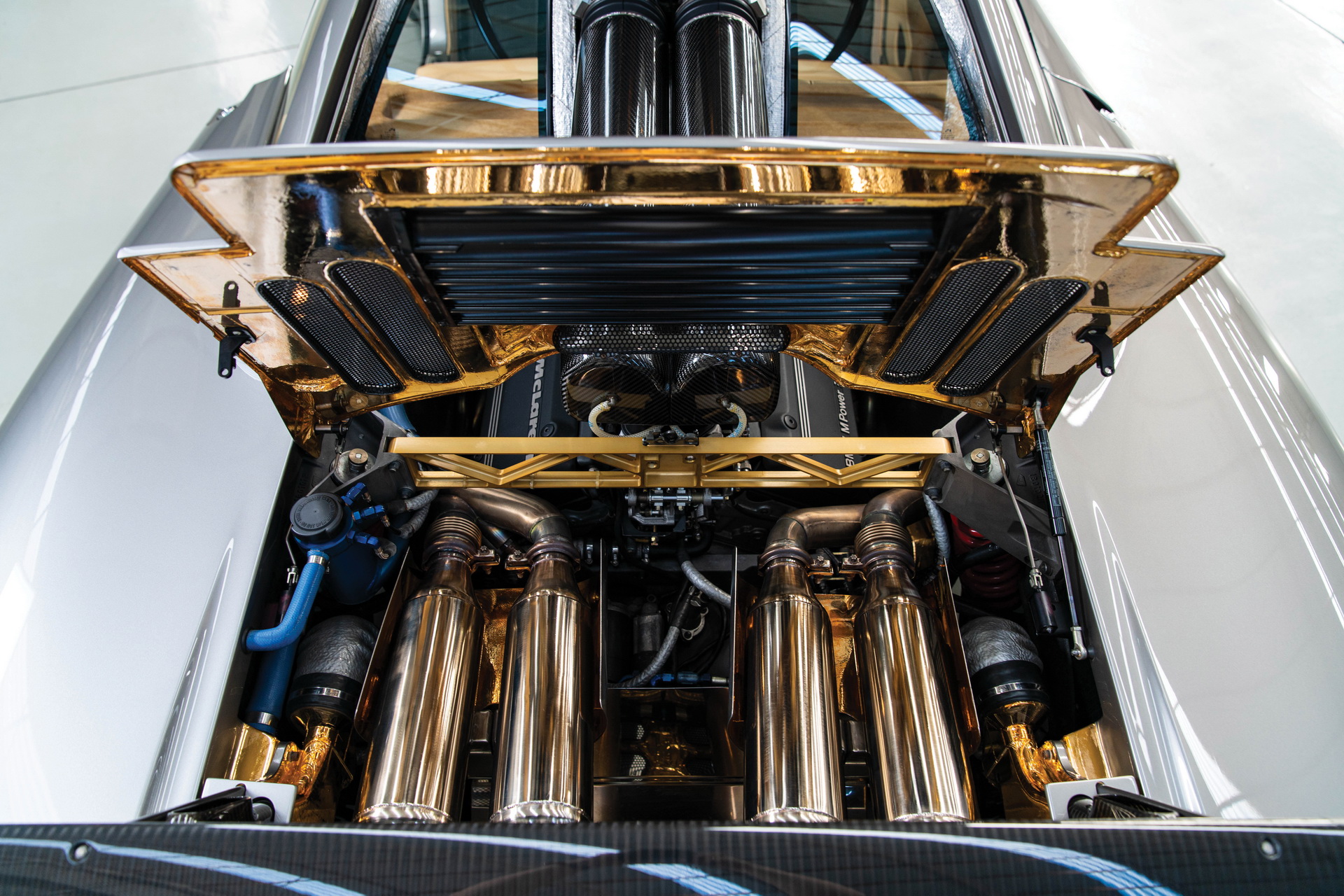

7. The engine bay was lined with gold

These days, when supercars are as much about showing off as showing someone your tail lamps in a roll-on race, a gold lined engine bay sounds entirely appropriate. But Murray and his team opted for gold because of its ability to reflect heat.

8. Even the toolkit was made from fancy metal

Related: These Independent Renderings Make Us Wish McLaren Made An F1 Roadster

Each McLaren came with a tool roll full of lightweight titanium wrenches – not that we can imagine many customers using them regularly. One set sold at auction through RM Sotheby’s earlier this year for £6,000 ($7,600).

9. McLaren’s version of AAA came by plane

Broken down in the middle of nowhere on a road trip? No problem. McLaren employed a team of flying F1 doctors who were ready to be dispatched around the world at a moment’s notice to help fix any broken cars.

10. Weird mix of mundane and motorsport parts

Although the engine bay was lined with gold, the body made from carbon, and the fuel tank was a racing-style bag tank that had to be replaced every five years (an expensive engine-out job), not everything about the F1 was exotic. The McLaren’s off-the-shelf rear lights could also be found on the Dutch Bova Futura bus and the door mirrors came from a VW Corrado coupe.

11. It weighed almost the same as a 2022 Miata

The F1 tipped the scales at 2,509 lbs (1,138 kg), which means a V12-powered McLaren supercar complete with driver weighs the same as a four-cylinder Mazda MX-5 RF running two-up. The lightest of McLaren’s current cars, the Senna, is 397 lbs (180 kg) heavier, and the 2005 Bugatti Veyron that succeeded the F1 as the world’s fastest supercar carried a massive 1,650 lbs (750 kg) weight penalty, the equivalent of driving around with a S1 Lotus Elise in the passenger seat.

12. The Hi-Fi was custom-designed for 220 mph duties

There was no radio on the F1, but McLaren commissioned Kenwood to develop a special lightweight 10-disc CD changer that could withstand 1.5 g of cornering force without, literally, skipping a beat.

13. It had a modem to tell McLaren about problems

Most houses didn’t have the internet in the early 1990s, and the over-air update technology we have on today’s cars sounded like a 25th century fantasy. But the F1 came equipped with a modem that could transmit info from the ECU back to HQ and tell McLaren what was up with a sick car.

14. The early development mules were Ultima kit cars

With no previous generation cars to turn into mules for the F1, McLaren purchased two Ultima kits from Noble Motorsport, which they christened Albert and Edward. Albert used a tuned Chevy V8 to test the new gearbox and was used to develop the three-seat layout, while Edward got the job of testing the real 6.1-liter V12. Murray again turned to Ultima when building a mule for the Gordon Murray Automotive T.50.

15. There were no visible wings, but plenty of F1-inspired ground effects

You won’t find a giant fixed wing on the original F1 road car, but there’s plenty of aero work going on behind the scenes, or more specifically, under them. The F1 employed ground effects lessons learned in F1, including two small fans that improved downforce by five percent. Murray had already employed fans on the 1970s Brabham BT46B racer, and recently revisited the tech with his T.50 hypercar.

16. It was inspired by the Honda NSX

The F1 is famous for going faster than any other supercar of the time, but just as important for Murray, was to set new benchmarks in usability, something Honda had done with the NSX. “The moment I drove the ‘little’ NSX, all the benchmark cars – Ferrari, Porsche, Lamborghini – I had been using as references in the development of my car vanished from my mind,” said Murray in an article posted on Honda’s Japanese website. “Of course the car we would create, the McLaren F1, needed to be faster than the NSX, but the NSX’s ride quality and handling would become our new design target.”

17. When Honda turned down Murray’s request to build a V12, BMW came up trumps

Honda, of course, had been working closely with McLaren for years as an engine supplier and was a key part of the team’s F1 success story. But when Murray approached them about building a V12 for his supercar project, the company refused.

Fortunately BMW picked up the baton and spectacularly overdelivered. The 6.1-liter S70/2 was very loosely based on the V12 in the 850 CSi, but gained four-valve technology courtesy of heads related to the S50B32 fitted to European-market E36 M3s. Without the help of turbos it made 618 hp (627 PS) at 7,400 rpm and 480 lb-ft (651 Nm) at 6,700 rpm.

18. It blew every other supercar out of the water

Zero to 60 mph (96 km/h) in 3.2 seconds is still strong performance today, even 30 years later, and particularly impressive when you remember it was achieved in a manual-shift car with no all-wheel drive or launch control. But it’s what happened beyond 60 mph that really set the F1 apart from every other supercar.

Related: This Porsche Boxster-Based McLaren F1 Replica Is Actually Quite Impressive

It passed 100 mph (161 km/h) in 6.3 seconds, around 4 seconds faster than a contemporary Ferrari F12M, and 3 seconds ahead of the Bugatti EB110 SS, the supercar whose performance crown the F1 stole. And in the 24 seconds your average hot hatch needed to hit 100 mph from rest in 1994, the F1 was touching 190 mph (306 km/h).

19. It was the world’s fastest production car for over 10 years

The original production-spec F1 would hit its 7,500 rpm rev limiter in sixth, limiting its top speed to 221 mph (356 km/h). That was already enough to make it the world’s fastest car, but in 1998, Le Mans racer Andy Wallace swallowed a year’s worth of brave pills and set off around VW’s Ehra-Lessien test track in a five-year old prototype with the rev limiter raised to 8,300 rpm, recording a two-way average of 240 mph (386 km/h).

Supercars have gone quicker since, including the Bugatti Chrion Super Sport 300+, which hit an absurd 304.77 mph (490.48 km/h) at the same track in 2019, again with Wallace at the wheel, but every one has done it with turbo assistance. The F1 is still the fastest naturally aspirated production car with evidence to prove it abilities, though Aston Martin claims an unverified 250 mph (402 km/h) for the V12 Valkyrie.

20. There were zero driver aids

Despite being head and shoulders faster than any other road car ever built, the F1 came equipped without traction control or ABS. It also had manual steering and didn’t even have a brake servo.

21. It was never designed to go racing but won at Le Mans

Like the original supercar, the Lamborghini Miura, the F1 wasn’t adapted from the track for the road, but designed from the ground up as a road car with no competition aspirations. Which makes the F1 GTR’s 1995 Le Mans win against dedicated competition machinery all the more incredible.

22. Le Mans success gave us an even hotter road car

McLaren commemorated its Le Mans success with five LM road cars, each painted in Papaya Orange and modified with a rear wing, stripped-down interior, magnesium wheels and a revised gearbox. It also featured a V12 uprated to 671 hp (680 PS), which made it more powerful than the actual race cars, whose air restrictors limited them to 591 hp (600 PS) to comply with competition regs.

23. Tougher competition on track led to the Long Tail

Today’s hardcore McLaren LT cars are inspired by the stretched Long Tail F1s McLaren developed to try to stay competitive on the track. The extended bodywork was the most obvious mod, but they also got a revised 6.0-liter V12 and sequential gearbox. McLaren also built two F1 GT road cars for customers featuring elongated bodywork to homologate the racing machines.

24. BMW later used the V12 engine for its own Le Mans winner

Things got tougher on the track for 1998 and McLaren pulled out of GT racing, sensing the F1 would struggle against a new breed of specially homologated racing cars like the Mercedes CLK GTR and Porsche 911 GT1.

But BMW took the V12 it had developed, made a few changes, dropped it into a Williams chassis to create the V12 LM, and paid Schnitzer Motorsport to run the campaign. It bombed, but its V12 LMR successor went on to score BMW’s only outright Le Mans victory in 1999.

25. And then BWW went nuts and put it in an X5

Okay, so we’re getting a little off-track here, no pun intended, but BMW’s decision to bolt an engine designed for the world’s fastest supercar that had gone on to powered two 24-Hour winners into the nose of an SUV was one of its craziest ideas.

Without the Le Mans cars’ air restrictors, the S70/3 V12 in the X5 Le Mans made over 700 hp (710 PS) and 531 lb-ft (720 Nm) of torque, and was hooked up to a six-speed manual transmission. Needless to say, it didn’t get past the concept stage, though BMW did treat journalists to demo laps at the Nürburgring.

26. Production wrapped in 1998 after only 106 cars

Unlike today, where there are plenty of $2m+ cars to buy, the world wasn’t really ready for a car like the McLaren F1 30 years ago. Factor in financial downturns and the result was that between 1992 and 1994 McLaren built just 106 cars including five prototypes and 64 road cars.

27. American versions were very rare, and very slightly slower

Related: First U.S. McLaren F1 Fetches A Staggering $15.62 Million

Only seven F1s were ever officially imported into the U.S., each one supposedly federalized by New York-based Ameritech. The cars lost their side seats and gained new lights, ugly bumpers and extra weight in the process, though the mods were non-destructive and we imagine every car has now reverted to the original factory spec, if they were in fact ever actually modded in the first place.

Road & Track’s 1997 test proved the U.S version could reach 60 mph (96 km/h) in 3.4 seconds, and 120 mph (161 km/h) in 10.5 seconds, compared with 3.2 seconds and 9.2 seconds for a European car.

28. They make perfect commuter cars

There’s an apocryphal story about wealthy banker and racer, Thomas Bscher, using his F1 for his daily commute between Cologne and Frankfurt, and cracking 200 mph (320 km/h) on almost every trip. Bscher also raced an F1 GTR, wining the 1995 BPR Championship, and was later in charge of Bugatti’s Veyron project.

29. You couldn’t afford one then and definitely can’t afford one now

The F1 was shockingly expensive when new, but the original list price (double the price of an EB110, remember) seems laughable compared to what F1s are fetching today. The perfectly preserved 1995 F1 pictured above had just 242 miles (390 km) on the clock when it sold at auction last year for $20,465,000, and a 1994 car converted to LM spec that had covered a more sensible 13,350 miles (21,500 km) achieved $19.8 million in 2019.

30. For many, it’s still the benchmark

The McLaren F1 is no longer the fastest, the most powerful, or the most expensive supercar. Others are even more rare and arguably better looking. But the F1’s purity – low weight, no turbo lag, manual transmission – means it still promises the kind of connected driving experience so many of its successors failed to deliver, and it still tops so many wish lists. Here’s to the next 30 years.