Governments and their agencies love making life hard for automakers in the name of supposedly making life better for the rest of us. There are rules about sound and exhaust emissions, and, of course, laws about safety. And to keep engineers on their toes, those regulations are constantly changing.

From this year any new car launched in Europe must now be fitted with Intelligent Speed Assist (ISA) technology to discourage drivers from enjoying themselves too much. But 50 years ago this fall automakers were dealing with legislation that would make their cars worse than slow. It would potentially make them hideous.

Starting with the 1973 model year, cars sold in the U.S. were required to meet new low-speed crash standards laid out by America’s National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard (FMVSS) 215 demanded that 1973 cars could withstand a 5 mph (8 km/h) head-on crash into a flat wall, suffering no damage to safety-related items like the horn, fuel system (including gas filler), and lights. The rear end, meanwhile, had to escape a 2.5 mph (4 km/h) hit unscathed.

It wasn’t damage to drivers’ bodies that the law was trying to prevent, but damage to their wallets during minor urban bumps that could land them (or their insurance companies) with a needlessly big bill. But meeting the requirements was going to hurt carmakers’ wallets, and the pain was going to get even worse for 1974 when the 2.5 mph rear end-test speed was doubled to 5 mph and the front end impact grew far more complicated.

Related: Watch The SCG 004S Supercar Pass A Side Impact Crash Test Without The Need For Airbags

Most collisions aren’t as straightforward as crashing into a flat wall, so the 1974 test introduced a huge, heavy pendulum with a 24-inch by 4.5-inch (610 x 114 mm) face that was hurled at the car seven times. Six of those hits were aimed at the front from different positions (and heights) at 5 mph, while the seventh smacked the corner at 30 degrees at 3 mph (5 km/h).

Although some smaller cars, including two-seaters and sporty hardtops with a sub-115-inch (2.92 m) wheelbase were granted a temporary exemption from the 1974 test, most carmakers knew they had to act sooner or later. And clearly those dainty little chrome bumpers they had been fitting to cars throughout the 1960s and into the early 1970s were never going to withstand an assault by wall and pendulum, particularly on cars whose lights were located inside, or attached to, the bumpers themselves.

But that doesn’t mean every car built after the legislation came into force was a disaster. Some looked terrible, but others came up with solutions so successful that they’ve become iconic design features. Let’s take a look at how different automakers responded to the challenge.

BMW 2002

BMW’s 2002 managed to move from 1972 (top pic) to 1973 (middle pic) mostly unscathed. The bumpers don’t look much different at first glance, though they were spaced further from the body in 1973 to give extra protection. But by 1974 (bottom pic) the 2002 was blighted with a pair of hideous girders mounted on energy absorbing rams.

Chevrolet Corvette

Chevy’s solution for the C3 Corvette was arguably the best that any carmaker came up with. Model year ’73 cars lost the chrome front bumper that had been fitted since the C3 made its debut in 1968 and until 1972 (top pic), replacing them with a body-color front bumper that fitted flush with the bodywork (middle pic). And to comply with the following year’s tougher rear-impact legislation, 1974 cars made the same switch at the back. Although the combined effect dramatically increased the length (and weight) of the C3’s overhangs, this was still one of the neatest bumper fixes.

MG B

Though MG Bs made it through to late 1973 (top pic) with their looks intact, January 1974 brought huge rubber yoga blocks (nicknamed “Sabrinas” after a shapely British pin-up) just like the ones forced on Jaguar’s E-Type the same year. But they were just a stopgap until the infamous rubber (but actually plastic) bumpers and a 1.5-inch (38 mm) ride-height boost arrived in the fall of that year. MG apparently tried painting the new bumpers to match the body of each car, but couldn’t perfect the process and left them black.

Mercedes SL

The R107 Mercedes SL was a beautifully understated bit of design, and apart from being stuck with four sealed beam lights (blame the same 1968 laws that killed the Ferrari Daytona’s plexiglass nose) and some discrete overriders, U.S. cars looked much like the European-market models for the first couple of years. But 1974 cars grew 8 inches (203 mm) in length with the addition of ugly diving board bumpers.

Porsche 911

Related: Rimac Completes The Final U.S. Crash Test For The Nevera Supercar

The “impact bumper” 911s, as they’re known by fans, might not be as pretty as the pre-’74 cars, but the design is equally loved. That’s partly down to how well executed it was (covering the gaps between car and bumper was a masterstroke), and also how long-lived: the design lasted for 15 years with almost no changes.

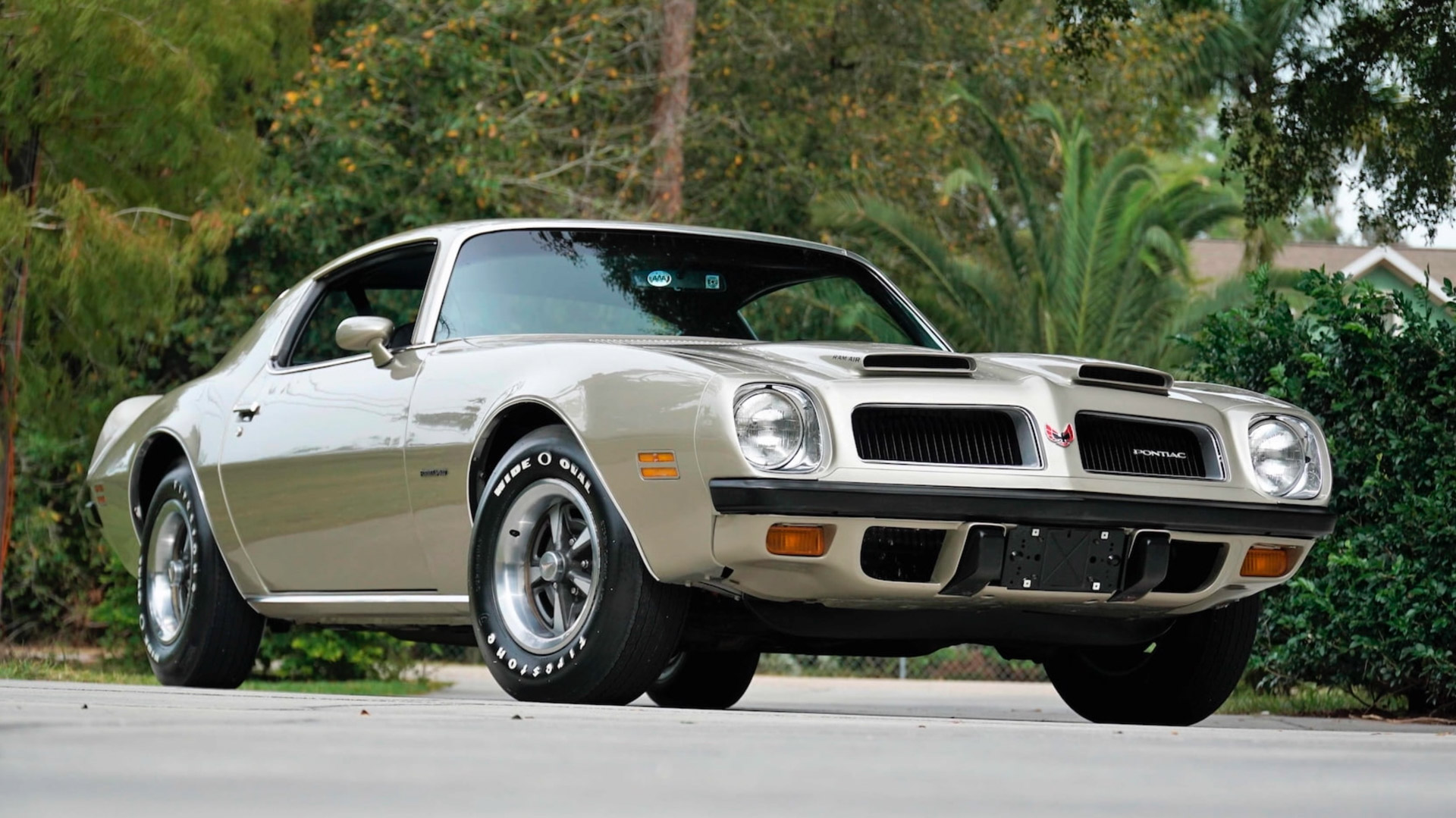

Pontiac Firebird

Pontiac had actually pioneered body-color Endura bumpers that could withstand small impacts on the the 1968 GTO, and applied the same tech to the 1970 Firebird (top pic). With only subtle visible changes that same snout survived until 1973 (you can tell the ’73 in the middle image by its recessed grills bezels), but to meet the tougher test, including the corner attacks, ’74s got a new front end with a wraparound bumper that wasn’t body color, but was still very artfully done.

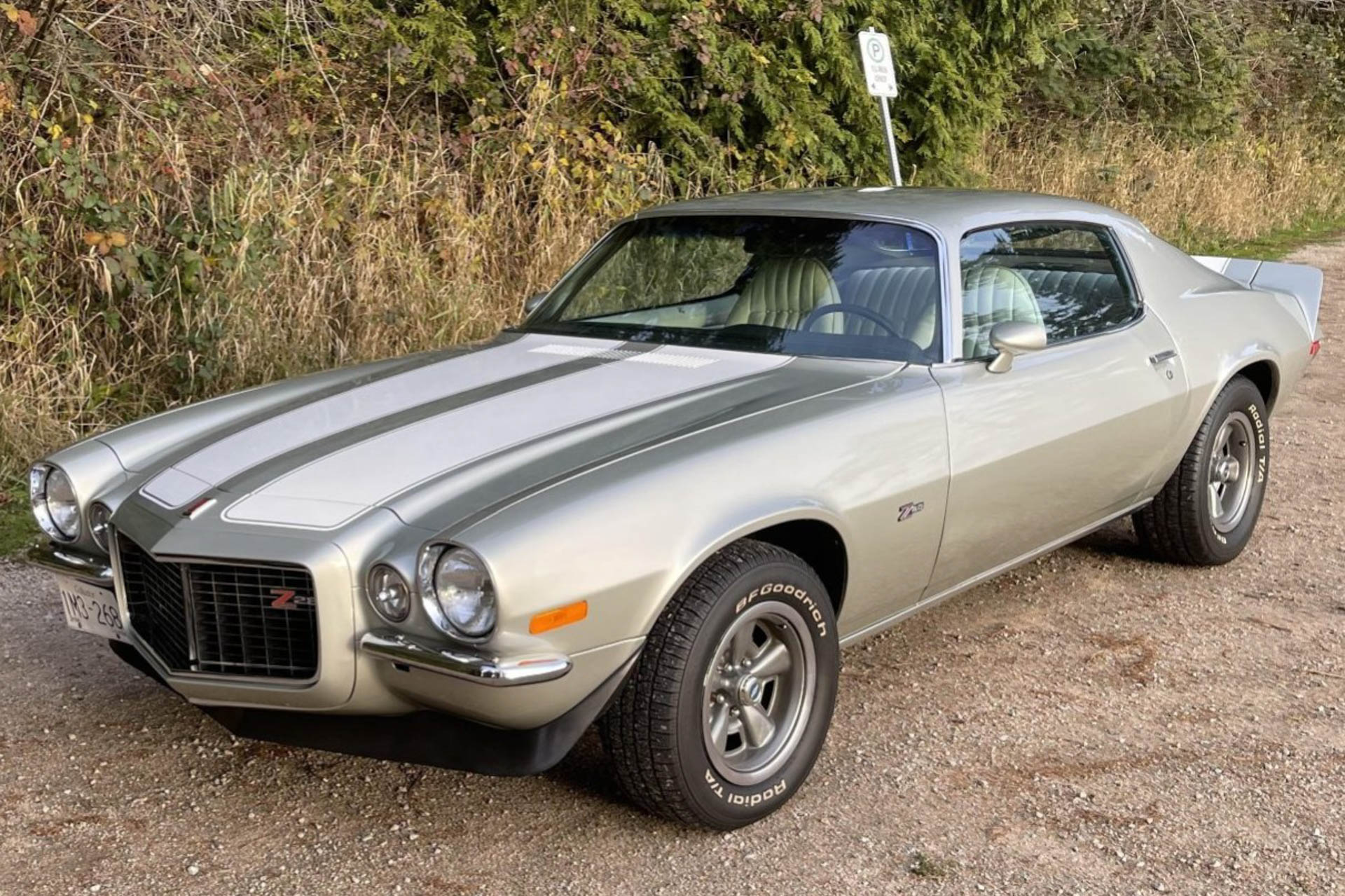

Chevrolet Camaro

The Firebird’s Camaro cousin wasn’t quite so lucky. Maybe Chevy’s engineers were too busy working on the Corvette, or the 1974 Chevelle Laguna, which also employed a urethane nosecone to great effect. Like the Firebird, the Camaro switched to a shovel-nose look, which meant it lost the cool optional RS front end with its split bumper treatment. Instead, all 1974 Camaros came with a huge rectangular expanse of steel stretched across the nose, plus another one at the back.

Lincoln Continental

You only have to look at three pictures above to see what a dramatic effect the new bumper rules had on car styling. The ’72 Continental’s bumpers closely followed the crisp lines of the front sheetmetal which ran from the base of the A-pillar to the bottom of the fender just ahead of the front wheel. It looked classy, but probably afforded next to no protection in minor fender benders. Fast forward to 1974, they’ve turned into full-blown freeway guard-rails that barely make any attempt to integrate with the design of the body.

Fiat X/19

Fiat’s X1/9 baby sports car arrived in European dealerships in 1972 wearing a quartet of elegant corner bumpers and reasonably subtle black overriders. But when Fiat finally got around to modifying 1975 model-year U.S. cars to meet the ’74 regs it did so by bolting what looked like a pair of toy stepladders to each end of the car.

Datsun 260Z

Related: Try Not To Weep At This Graveyard Of Ferrari 812 Competizione Crash Test Cars

Like the European brands, Japanese automakers struggled to come up with aesthetically pleasing solutions to regulations that didn’t effect their home-market cars. The 1974 260Z started off looking much like the earlier 240Z, but was soon afflicted with nasty rectangular metal bumpers front and back.

De Tomaso Pantera

Making a sleek sports car comply with the bumper regulations was trickier than fixing a big, boxy sedan, but the Corvette and 911 designers and engineers weren’t the only ones who got it right. De Tomaso also did a pretty good job when it realized the original Pantera’s itsy-bitsy bumperettes weren’t going to be man enough to meet the new legislation.

The rear bumper wasn’t hugely elegant (though better than most sports car solutions), but the front one neatly followed the lines of the fenders and hood, just like the Corvette’s, and still managed to look pretty cool even though it wasn’t painted in body color.

Citroen, Ferrari and Lamborghini

Some foreign automakers didn’t even attempt to homologate their cars, deciding that the cost of meeting both the crash legislation and increasingly strict emissions rules wasn’t worth the bother, or was simply unaffordable. The Citroen SM’s hydropneumatic suspension meant it was too low, as was the Lamborghini Countach, though some Countaches were federalized with the addition of a very strange add-on bumper by third party companies, including the famous Cannonball Run Countach. And Ferrari opted not to bring either the 365 GT4 2+2 grand tourer or 365 GT4 Berlinetta Boxer to America, though it did modify the little Dino 308 GT4 to keep it U.S.-legal, making an already awkward car even uglier.

Who do you think handled the 5 mph bumper laws best, and who got it really wrong? Leave a comment and let us know.