Electric power has already transformed the passenger car market, and big trucks are next. Tesla will officially unveil its Semi EV on December 1 and hopes to pump out up to 50,000 electric trucks per year as early as 2024. And it’s far from the only company electrifying commercial vehicles.

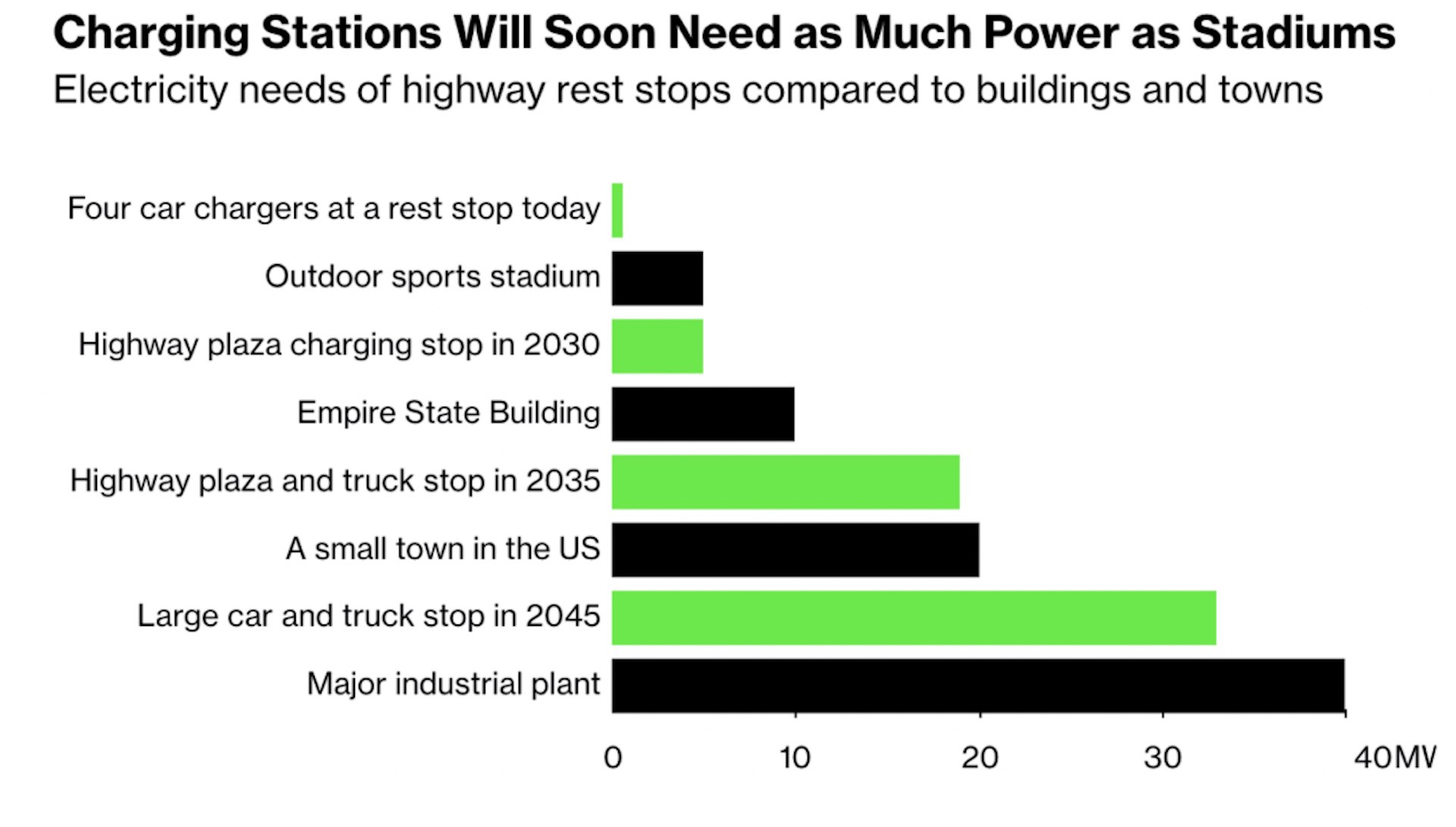

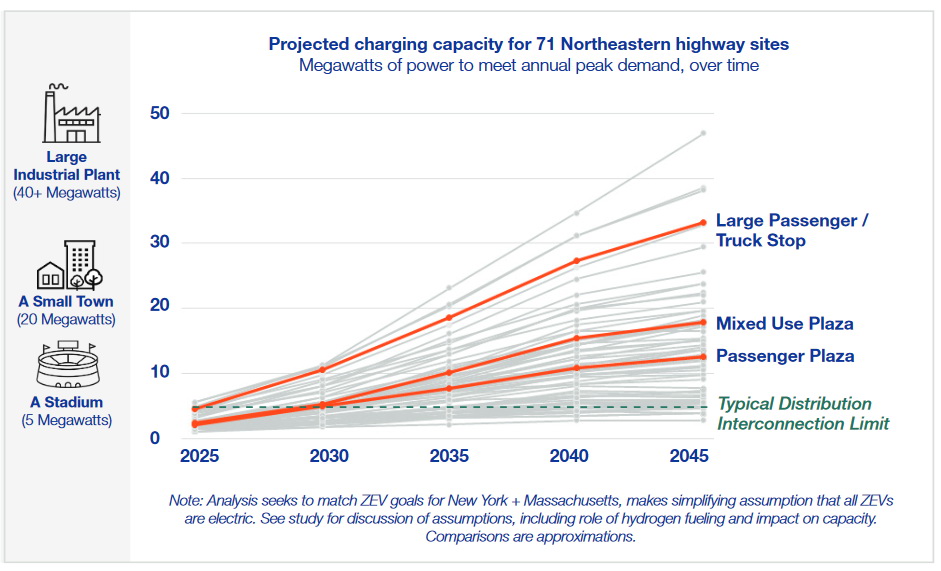

Come 2030 or 2035, buying an electric truck won’t be a problem, but charging it might be, according to a report by National Grid. The study says that the electric truck market could find itself limited by an inadequate charging infrastructure in the next decade if major investment doesn’t happen now. Why? Because it estimates that a truck stop in 2035 might need as much electricity as a small town.

It’s not the amount of electricity that we’re going to need that’s the problem, but how quickly we’re going to want to deploy it in one place, like a truck stop full of vehicles that are effectively gargantuan 18-wheeled batteries.

Bloomberg’s smart analogy likens electricity to water flowing through a hose, pointing out that you could use that hose to fill a swimming pool if you had a few months to spare, but filling that pool in a a few hours is a different story. To do that you’re going to need the electric cable equivalent of a riot-police water canon.

So let’s get building, you’re thinking. The problem is we should have been building years ago. A connection to the grid capable of dealing with more than 5 megawatts of power might take eight years to plan and build, and cost tens of millions of dollars. And recent incentives from the U.S. government designed to promote a switch to electric power has fast tracked a move to commercial EVs that might take place before the charging network has been upgraded to accommodate them. That’s despite President Biden’s 2021 infrastructure package earmarking $7.5 billion to pay for a national charging network and upgrades to the grid.

“We need to start making these investments now,” Bart Franey, vice president of clean energy development at National Grid, told Bloomberg in an interview. “We can’t just wait for it to happen, because the market is going to outpace the infrastructure.”

Some fleet operators are already experiencing problems, Rakesh Aneja, head of electric trucks at Daimler North America, admitted. The company currently offers electric trucks in the U.S. but some customers were dismayed to discover that it would take a year longer to connect their chargers than it would to receive their Freightliner eCascadia trucks.

“The number one concern for fleets wanting to electrify all of their vehicles is the infrastructure required,” Brian Wilkie, director of transport electrification at National Grid, told Bloomberg. “They know they can’t sell trucks without the power to charge. If they can solve that piece, they can scale the market much more quickly.”