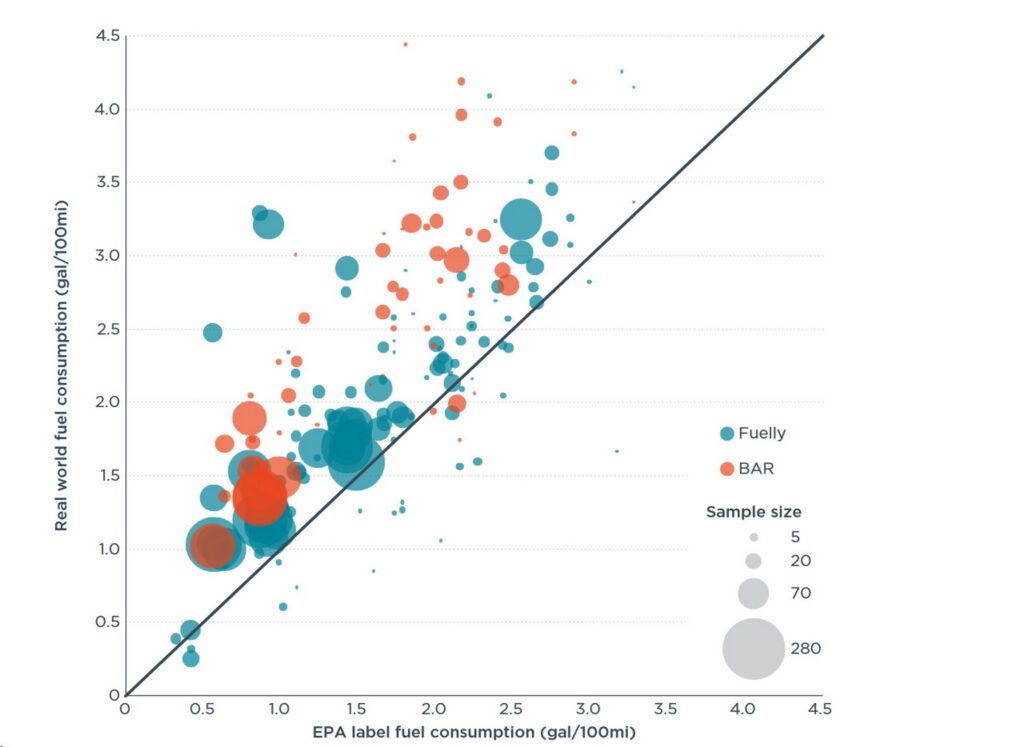

Data gathered by the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) suggests that the drivers of plug-in hybrid vehicles use their electric powertrain far less than previously assumed. That means that the vehicles are using more gas for their internal combustion engine than regulators at the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimate in their labeling program.

The study found that, in the real world, the share of driving handled entirely by electric motors is 26 to 56 percent lower than the EPA assumes when it is labeling the fuel efficiency of the vehicles. As a result, the real world fuel consumption tends to be 42 to 67 percent higher than the regulator estimates.

“New, growing datasets indicate PHEVs are not achieving the emissions reductions they are assumed to generate for compliance and labeling purposes,” the study’s authors write. “The trends in the new PHEV data clearly point to the need for much closer inspection and broader investigation into PHEV usage to inform regulatory treatment.”

Read: U.S. Fleet Efficiency Remains Stagnant For 2021 Model Year

Accurate measures that reflect how customers really use plug-in hybrid vehicles matter to policymakers, because the partially internal combustion vehicles are often lumped in with zero-emissions vehicles like EVs and hydrogen vehicles.

The vehicles are included in emissions reporting for automakers, receive environmental tax breaks, and, in Oregon (among other jurisdictions), dealers will be able to continue selling PHEVs even after the sale of new fully internal combustion engine vehicles is banned in 2035. The study’s authors, therefore, highlight a few steps that could be taken to more accurately assess the fuel economy and emissions of PHEVs.

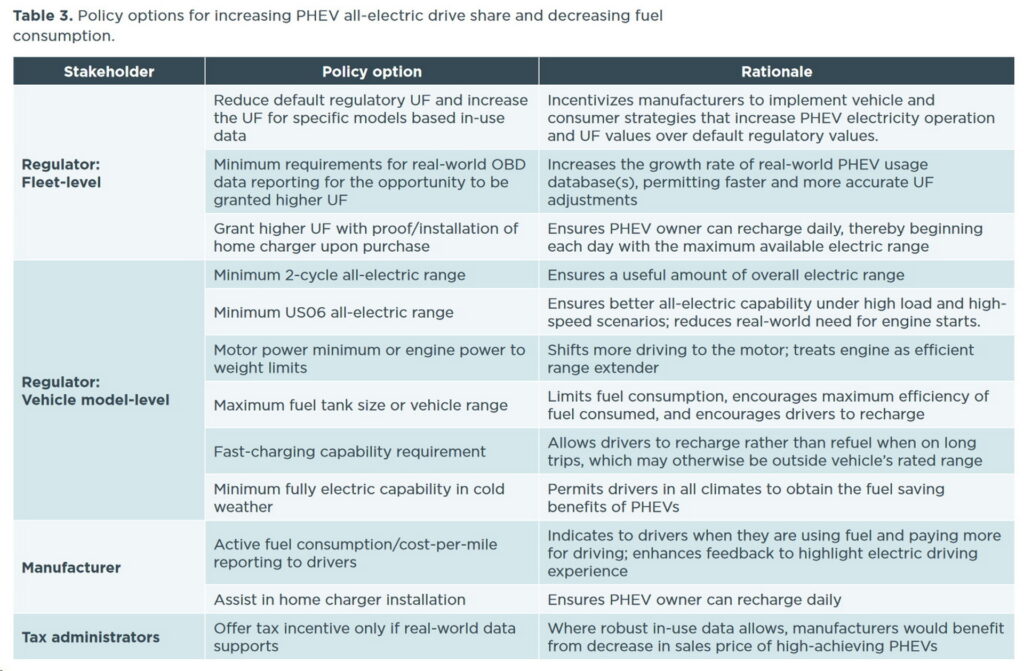

The ICCT suggests, for instance, that automakers could be required to report data of vehicles in the field, and minimum electric driving range requirements for vehicle crediting – a system that was first pioneered in California – could be introduced. The EPA could also adopt maximum engine power-to-weight limits, or outline how buyers with level 2 at-home chargers are likely to get better fuel economy than those without. Simplest of all, the EPA could just adjust its fuel economy figures on PHEVs to be lower than they currently are.

Automakers, too, could participate in increasing the use of the electric drivetrain in their PHEVs, by reporting the cost of not charging to users, perhaps within the vehicle’s infotainment screen.