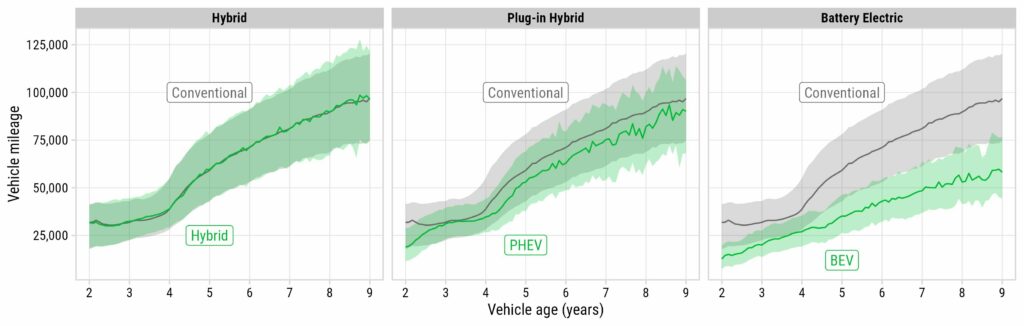

A recent study conducted in the United States has revealed that battery-electric vehicles (BEVs) tend to travel fewer miles per year in comparison to their gasoline-powered counterparts, including hybrids and plug-in hybrids.

The peer-reviewed study from researchers at the George Washington University (GW) used odometer readings from 12.5 million used cars and 11.4 million used SUVs listed up for sale between 2016 and 2022. It found that while most ICEs, hybrids, and PHEVs are driven similarly, battery-electric vehicles typically average 4,477 fewer miles (7,205 km) annually.

Researchers speculate that this difference may arise from the common practice of BEV owners using them as secondary vehicles alongside conventional or hybrid counterparts. Additionally, they have proposed that factors such as range anxiety and the relatively less developed charging infrastructure, in contrast to the well-established gas station network across the United States, might contribute to this phenomenon.

Read: Over Half Of EV Buyers Are Purchasing An ICE As Their Next Vehicle

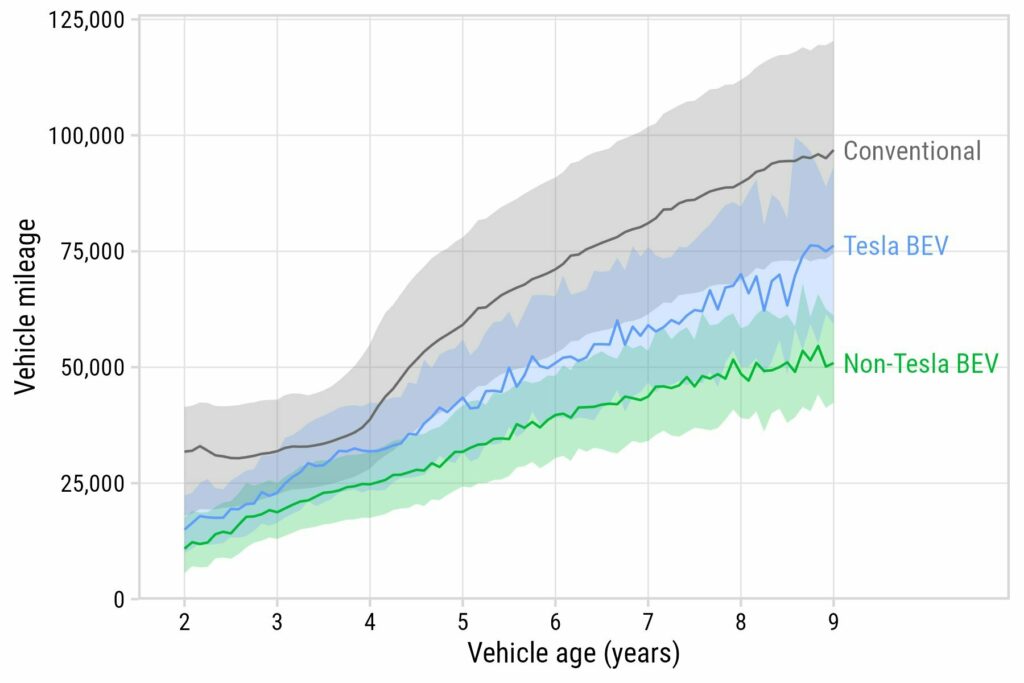

John Helveston, study co-author and Assistant Professor of Engineering Management and Systems Engineering at GW, says the average combustion car was driven 11,642 miles (18,735 km) annually while the average BEV was driven 7,165 miles (11,530 km). The gap was less pronounced in the SUV segment with the average ICE driven 12,945 miles (20,832 km) per year and the typical BEV driven 10,587 miles (17,038 km) per year. Interestingly, the average Tesla was driven 8,786 miles (14,139 km) per year compared to the 6,235 miles (10,034 km) of all other non-Tesla BEVs.

“People often assume that buying an EV is good for the environment, and it generally is, but the impacts scale with mileage,” Helveston said. “Our study shows that the current generation of EV owners aren’t using them as much as gas cars. For maximum impact, we need the highest-mileage drivers behind the wheel of EVs rather than low-mileage drivers.”

The researcher added that studies like this should be used by policymakers and regulators to draft and implement emissions regulations. For example, the latest analysis from the EPA assumes EVs are driven the same number of miles as ICE cars but this isn’t the case.

“If you’re going to craft a model that predicts how much emissions can be saved from EV adoption, that model heavily depends on how much you think EVs will be driven,” he noted. “If federal agencies are overestimating true mileage, that results in overestimating the emissions savings. We need to better understand not just who is buying EVs, but how they’re driving them. What trips are EV owners substituting for a cleaner trip in an EV, and what trips are EV owners not taking?”