- Insurance companies are using smartphone apps to collect additional driver data.

- That information ends up contributing to rates.

- Some applications track and record speeding, hard braking events, and location.

Smartphones enable incredible things, but there is another, darker side of that coin. They also open us all up to potential pitfalls. In several cases, they collect, store, and transmit data without ever telling the user. Now, insurance companies are using that data to set rates and create driver scores. You could have one such score without ever knowing it too.

For some, this might seem inevitable or obvious. Over the last two decades, insurance companies have tried to encourage drivers to use OBDII monitors in their cars. The incentive was potentially lower rates. The adoption rate for such devices has grown. but companies want more data.

More: Did OnStar Spy On You? GM Faces New Lawsuit Over Driver Data, Rising Insurance Rates

As a result, they’re turning to smartphone apps that ride along with users wherever they go. These aren’t insurance applications either. According to the New York Times, they’re ones like GasBuddy, Life360, and MyRadar. Each has opt-in features from a company called Arity, founded by Allstate in 2016, that rely on smartphone sensor data. Arity can then use that same data for insurance purposes.

It’s capable of recording not just where you drive but how fast you drive, how hard you brake or accelerate, and how much you use your phone while driving. Arity is quick to point out that users have to agree to a privacy statement before it can collect that information but of course, that agreement is in small print and really only available if the customer clicks a hyperlink to go read the statement.

On top of that, it sells driver scores to insurance companies via Allstate’s website. The other apps mentioned in the NYT story also submit data to Arity. “No one who realizes what they’re doing would consent,” said one Life360 customer, who canceled her subscription.

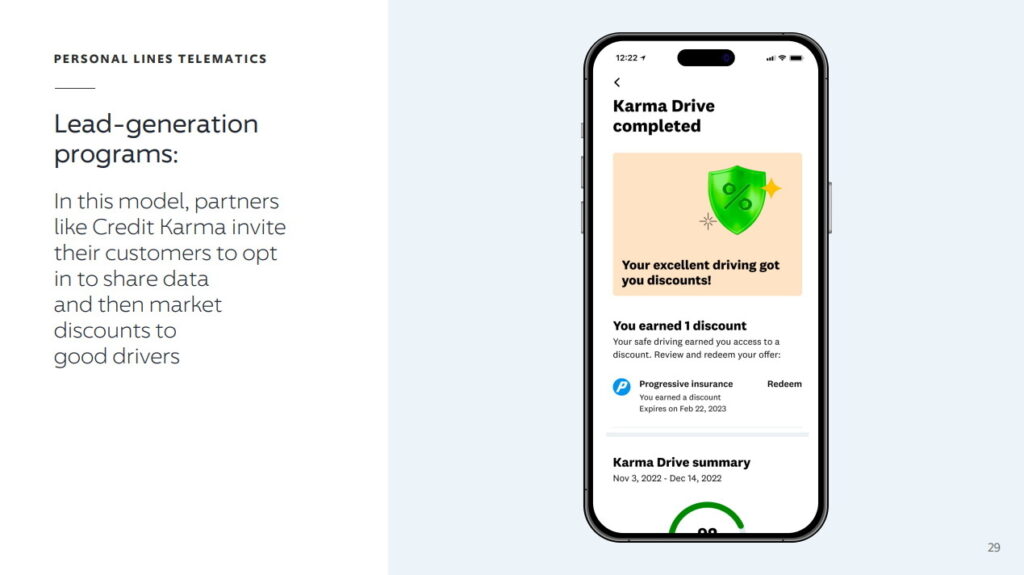

Credit Karma also offers a potential insurance discount through in-app monitoring. Interestingly, not every insurance company is using this sort of data, for now. USAA and Geico say they only use driving data from apps intended to track such behavior.

That likely won’t soothe the minds of the privacy concerned. In one case, a man named Rob received a message in his email from Toyota saying “Good news, Robert! You’ve been identified by Toyota Insurance as a safe driver.” Wondering how this was possible, he dug deeper and found that a company had captured his driving data, from his car, and used it to create that profile.

Read: 1 In 5 Crashed Cars Now Totaled By Insurance Firms, ADAS Partly To Blame

That company is Connected Analytic Services, a Toyota affiliate, and the data it collected was very detailed. It knew how far he’d driven, how many times safety systems engaged, and how many times he hit the brakes or accelerator “harder than necessary for defensive driving.” The report also included an Excel file showing his precise location for every recorded event and over 200 entries for the times when he drove above 85 mph.

The Argument For This Data

Not everyone is against the idea of having a rate based on their own driving habits. Data suggests that most people believe that they’re above-average drivers. Obviously, that can’t technically be true. but for some. a discounted rate could indeed be warranted. “Don’t judge me based on everyone else,” said one insurance consultant. “Judge me based on me.”

“There’s a lot of unfair discrimination in auto insurance,” Mr. DeLong of the Consumer Federation of America told the newspaper. “Auto insurance companies use a lot of socioeconomic factors, like your credit score or your job or your education level, like whether you went to high school or to college or whether you’re married. Telematics has substantial promise for consumers, and it could be a way to better price auto insurance,” he said.

What To Do For Now

Be sure to check your vehicle’s infotainment system for a way to opt in or out of data collection programs. Repeat that process when it comes to smartphone apps that request access to GPS or sensor data. Some will have an option marked “Do not sell my personal information.” Finally, some companies like Google claim that they don’t provide personally-linked data to third parties.