In the run-up to the release of the 2024 Bugatti W16 Mistral the guys at Molsheim dropped a big hint to their plans by celebrating the 10th birthday of the Veyron Grand Sport Vitesse, which achieved a record-breaking 254.04 mph (408.84 km/h) at Volkswagen’s Ehra-Lessien test track in 2013. That literally hair-raising top speed made the Vitesse the world’s fastest production convertible, an honor it holds to this day, as we reported just before Monterey Car Week.

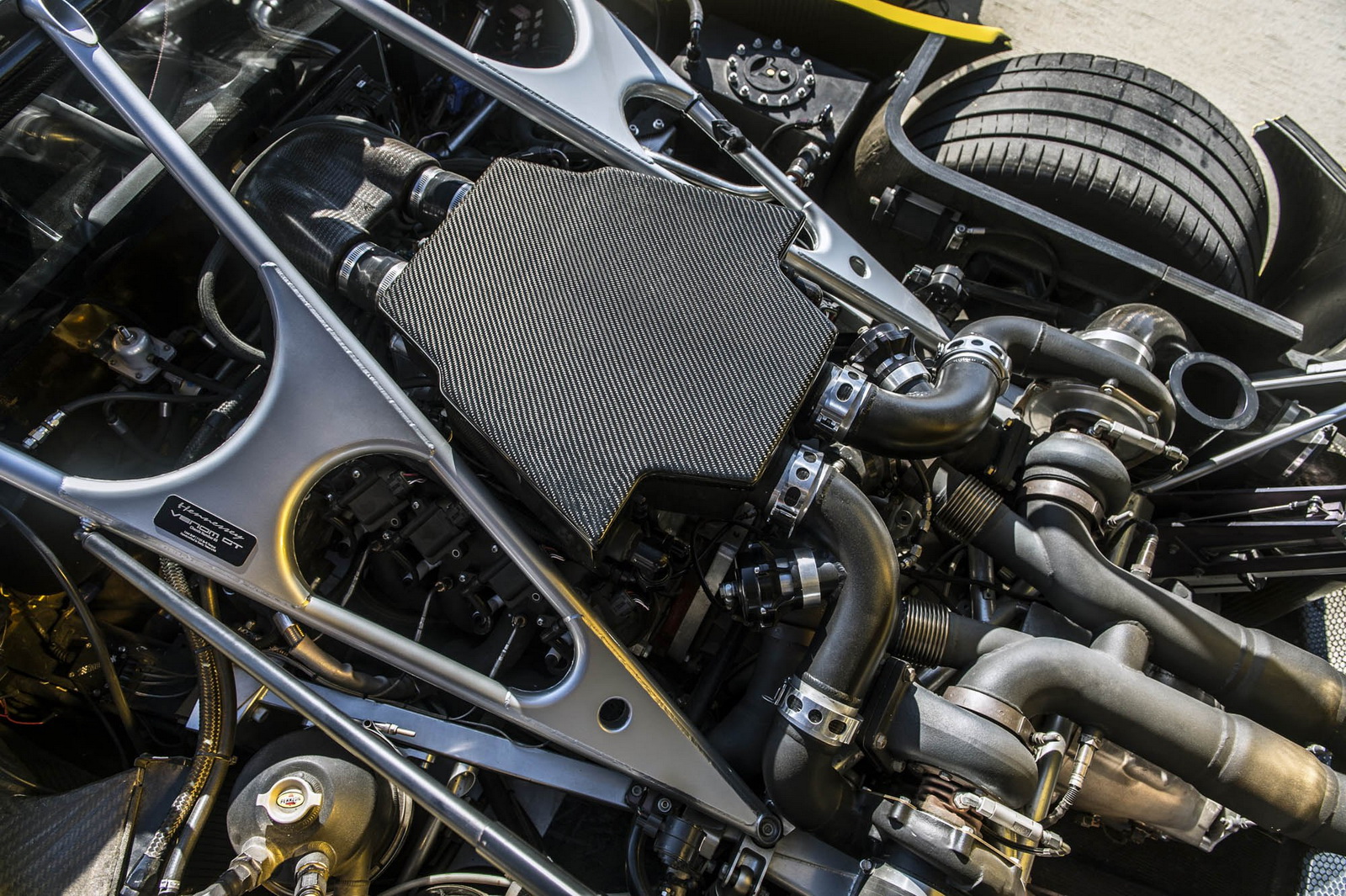

“Hold it right there!” said Hennessey, or words to that effect, in an email to us after we posted about Bugatti’s anniversary. Mike Harley, VP of Marketing and Communications for the power-crazed Texan company reminded us that the Hennessey Venom GT Spyder had broken the Veyron’s record in March 2016 when it reached 265.57 mph (427.4 km/h) at Naval Air Station Lemoore in California. And Hennessey hopes to smash that record again with its own new high-speed convertible, the 1,817 hp (1,842 PS) twin turbo 6.6-liter Venom F5 Roadster.

So had Bugatti simply forgotten about Hennessey’s record run, or was it choosing to ignore it for some reason? The company made clear at the launch of the Mistral that one of the key project goals was to build the world’s fastest convertible, but it clearly believes it only has to surpass the Veyron Grand Sport Vitesse’s speed, and not the Venom GT’s, to reach that goal. We asked Bugatti why it believed it was still the record holder despite Hennessey having video and data proof that it had gone faster, and a spokesperson told us:

“Bugatti produced 150 examples of the [convertible] Veyron 16.4 Grand Sport and Grand Sport Vitesse, and 300 examples of the Veyron 16.4 coupe, so the model is considered a production car.

“[Hennessey] produced significantly fewer vehicles, so it is not really considered a production series car. Furthermore, Bugatti’s top speed was recorded and verified by the independent German TÜV Saar.”

Let’s take a look at the production angle first. Bugatti built 450 Veyrons, 92 of which were the Grand Sport Vitesse that the company believes still holds the record. Hennessey, on the other hand, built only six Venom Spyders, plus seven coupes – rather less than the 29 Venoms Hennessey suggested it would build at the time.

There is no official definition (by volume) of what constitutes a production car, but Bugatti certainly looks more credible here, and, you might well note that the Veyron, like the new Venom F5, is a unique car, whereas the older Venom GT is loosely based on another manufacturer’s car (the Lotus Exige). But since Hennessey built several examples of the Venom, each with its own VIN number, it believes it is perfectly within its rights to call the Venom a production car.

Then there’s the issue of who ratifies the records. There is no one organization responsible for ratifying these kind of speed records across the globe. Essentially, anyone with a data logger and couple of GoPros can claim to have set a speed record. Bugatti’s run was observed by TÜV, a group of companies which has been involved in the business of testing and certifying machines and processes for almost 160 years. If TÜV Saarland said the Grand Vitesse did 254 mph then you have no reason to doubt it and can be damn sure internet sleuths won’t later discover that the true speed was at least 50 mph (81 km/h) lower, as happened to SSC and its farcical Tuatara top speed run in Nevada.

Hennessey didn’t have TÜV on hand in California in 2016, but it points out that its run was verified and certified by respected vehicle data outfit Racelogic. What’s more, Racelogic’s own technical director was on hand to do that verifying, whereas SSC simply used Dewetron’s timing gear, and not its operatives.

Related: Hennessey Chops The Roof Off Venom F5 To Create $3 Million Roadster

What about Guinness, they of “most donuts consumed in one minute” fame? Can’t we just hand over the verification of top speed records to the people known for marshaling crazy feats in every other field? We could, because Guinness World Records does ratify speed records, but you’ll note that neither of the convertibles duking it out in this post feature in Guinness’s database of speedy cars.

The reason is that certain conditions must be met for Guinness to ratify a record. I asked Guinness for a full list of rules a car must satisfy to become the world’s fastest car, but its team was unable to provide them because the criteria is currently being updated. But looking at recent records, one of those is that the car in question must have its speed recorded in two directions on the same stretch of road within 60 minutes to record an average.

Both the Grand Vitesse and Venom Spyder recorded their runs in one direction only, as did the the Venom GT coupe (which recorded 270.49 mph / 435.31 km/h in 2014) and the 304.77 mph (490.48 km/h) Chiron Super Sport 300+, which is why none of them are acknowledged as record breakers by Guinness.

Hennessey Venom F5 Roadster (top) and Bugatti W16 Mistral both want to be crowned world’s fastest convertible

Cars must also be in showroom stock condition, in the same spec that owners receive their cars, for a record to count. Back in 2013 Guinness voided the Veyron 16.4 coupe’s 267.8 mph (431 km/h) run from 2010 and its “world’s fastest car” title after discovering that production cars were equipped with 258 mph (415 km/h) speed restrictors not fitted to the record car. Production versions of the Super Sport 300+ were also limited, in that case to 273 mph (440 km/h).

And while there might not be an industry definition by volume of what constitutes a production car, Guinness does have its own definition. Guinness insists that at least 30 examples must be built for a car to qualify for a record attempt in its eyes. We don’t yet know whether Bugatti and Hennessey will ask Guinness to adjudicate on its future records, but based on the planned production volumes (99 Mistrals, 30 F5 Roadsters), both would satisfy Guinness’s production requirements.

Hennessey needs to top older Venom Spyder’s 265.57 mph (427.4 km/h) for F5 Roadster to be world’s fastest, but Bugatti might be happy with beating Veyron’s 254.04 mph (408.84 km/h) record

Neither company has made any top sped claims for their new models, but a line in Bugatti’s press release stating that the instruments are designed to be “easily visible at up to 420 km/h (260 mph)” leads us to think that the company might be targeting a top speed only slightly higher than the 254.04 mph (408.84 km/h) achieved by the Veyron Grand Sport Vitesse in 2013, and potentially less than the 265.57 mph (427.4 km/h) recorded by the Venom GT Spyder three years later.

Or perhaps a production version will be limited to 260 mph, but a record attempt might be made with a derestricted car capable of going faster, though for aerodynamic reasons, it won’t come close to the 304.77 mph (490.48 km/h) of the Chiron Super Sport 300+ despite packing the same 1,579 hp (1,600 PS) quad-turbo W16 motor. Hennessey, meanwhile, claims a 311+ mph (500 km/h) top sped for the Venom F5 Coupe and says the F5 Roadster is “engineered to exceed 300+ mph (483 km/h),” though that will be with the roof panel in place.

Do you believe the Bugatti Veyron Grand Sport Vitesse or the Hennessey Venom GT Spyder is the legitimate holder of the fastest production convertible record? And how many cars do you think an automaker needs to build for a model to be considered a production car? Leave a comment and let us know.